Researcher's work predicts how quakes shake different parts of NZ

If we want to predict how an earthquake will shake different parts of the country, it really helps to know the local soil and rock conditions. This is because the top 100-200 meters of soil can greatly amplify impact the strength and length of shaking – this is known as ‘site effects’, and it’s part of the reason why Wellington’s buildings were so badly damaged following the 2016 Kaikōura earthquake.

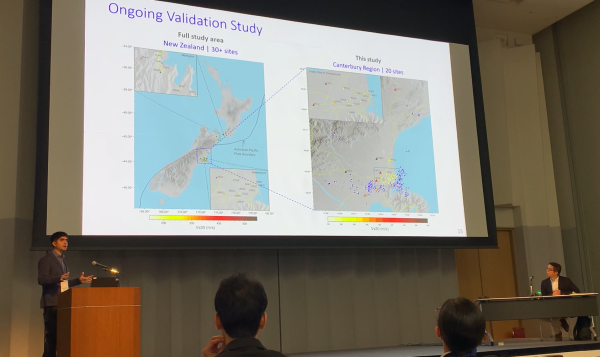

Doctor Felipe Kuncar spent his PhD at the University of Canterbury studying different soil profiles around New Zealand and incorporating them into ground shaking simulations, which can then be fed into tools like the National Seismic Hazard Model. His important work will contribute to more accurate and site-specific estimations of ground shaking.

Dr Kuncar is one of the brilliant minds behind the research we fund, and he’s this month’s featured NHC researcher. Read his interview with us below.

What do you like most about your work?

I really enjoy staying up to date with the latest advances in my research field and working at the forefront of knowledge. It is very exciting to feel that I can contribute to advancing our understanding of complex problems that directly impact society and developing tools that can be used to reduce damage and save lives.

Why is it important to invest in natural hazards research like yours?

Because it allows us to understand what to expect from future earthquakes without having to experience them first. This enables timely and informed decision-making that helps prevent disasters and reduce costs.

For example, we know that earthquake-induced ground shaking varies significantly across different locations. This means that, within the same city, some structures will be more impacted than others during the same earthquake. Improving our ability to predict ground shaking means that we can identify areas and sites that require more robust seismic designs, and in this way allocate resources more efficiently.

What is your personal experience with natural disasters, and how has it influenced your research?

As a Chilean, earthquakes have always been part of life. I was born in Valdivia, the city that gave its name to the largest earthquake ever recorded (the 1960 magnitude 9.5 Valdivia earthquake), and I grew up hearing family stories about that event.

In Chile, people are used to experiencing many tremors each year and major subduction earthquakes a few times during their lifetime. The 2010 magnitude 8.8 Maule earthquake had a profound impact on the country, and it deeply shaped my understanding of the critical role engineering plays in society.

What are your ambitions for your research or career?

I would like to continue doing cutting-edge research while ensuring that these findings are translated into engineering solutions. Too often, there is a gap between what we know and what we apply in practice. As an engineer, I would like to contribute to closing that gap. Also, I would like to stay closely connected to real-world engineering practice, which is essential to define meaningful and relevant research questions.

What is your vision for a resilient New Zealand – what does it mean/look like?

I envision a country that can live alongside the seismic hazards it constantly faces, where the loss of human life is prevented and communities are able to recover quickly after an earthquake. While it may be impossible to avoid all damage, having clear and accessible information about what to expect can empower both communities and decision-makers to act in advance and significantly reduce the impact of these events.

Do you have a favourite anecdote or memory related to your research?

One of the aspects I enjoy most about my work is attending conferences and connecting with researchers from around the world, at different stages of their careers.

In 2024, I had the opportunity to attend the International Conference on Earthquake Geotechnical Engineering, held in Japan, where I met two of the pioneers (and true legends!) of this relatively young field: Izzat Idriss and Kenji Ishihara. That memorable moment was captured in the above photo alongside my PhD supervisor, Brendon Bradley, and my colleague, Ayushi Tiwari.