Fine-tuning the mother of all earthquake models

Earthquake modelling is at the heart of how New Zealand manages seismic risk. Research engineer Dr Chris de la Torre from the University of Canterbury is contributing to that effort by improving the mother of all earthquake models – New Zealand’s National Seismic Hazard Model (NSHM).

The NSHM is New Zealand’s official, science-based estimate of how often and how strongly different parts of the country are likely to experience earthquake shaking. Its impact is hard to overstate – it’s used in everything from building standards, insurance prices, to long-term risk planning.

The NSHM is underpinned in part by NHC-funded research, and we continue to invest in keeping the model up to date with the latest science and data.

The NSHM is underpinned in part by NHC-funded research, and we continue to invest in keeping the model up to date with the latest science and data.

As part of that, we’re funding Dr de la Torre to help the NHSM better account for site responses – how local soils affect earthquake shaking. Soft soils don’t behave the same way in every earthquake: they often amplify shaking, but depending on the soil layers and the type of shaking, they can also reduce it. Because these effects vary from quake to quake, some areas might be over- or underestimated in the current NHSM. Chris is working with colleagues from University of Canterbury and Earth Sciences NZ to refine these estimates.

If incorporated into the NSHM, de la Torre’s work has the potential to influence many decisions around where and how we build in New Zealand.

Between his work and exploring the great outdoors with his son, Chris shares what drives research – and why you should never ask an earthquake engineer when the “next big one” will happen.

What is your NHC funded project, in a nutshell, and why is it important to New Zealand?

The main objectives of this study are to scrutinize the output of the New Zealand National Seismic Hazard Model (NSHM) and to improve the modelling of nonlinear site response in the NSHM and in downstream engineering design standards. Site response, i.e., how near-surface soils modify earthquake ground motions, can have a significant influence on the intensity, duration, and frequency content of the ground shaking.

The main objectives of this study are to scrutinize the output of the New Zealand National Seismic Hazard Model (NSHM) and to improve the modelling of nonlinear site response in the NSHM and in downstream engineering design standards. Site response, i.e., how near-surface soils modify earthquake ground motions, can have a significant influence on the intensity, duration, and frequency content of the ground shaking.

Therefore, modelling it correctly is critical, because it directly influences the seismic demands used in design. By improving how we represent these effects in the hazard model, we can make sure that design standards better reflect the true behaviour of New Zealand soils during earthquakes.

What’s your favourite part of being a researcher?

It’s difficult to choose just one, but my top three reasons for being a researcher are:

1. The opportunity to make scientific advancements that genuinely benefit society.

2. The excitement of learning new things and uncovering fascinating, complex phenomena, sometimes seeing something that no one else has noticed or explained before.

3. Collaborating with inspiring researchers from around the world to share ideas, gain new perspectives, and build strong teams capable of tackling the major challenges we face.

What sparked your interest in studying natural hazards?

The main reason I chose geotechnical engineering and then geotechnical earthquake engineering is that soils and earthquakes are very complex phenomena that are driven by natural processes. Geotechnical engineering is often called a kind of “black magic” because, unlike most fields in engineering, we work with materials that are hidden from view and never behave exactly the same way twice.

The main reason I chose geotechnical engineering and then geotechnical earthquake engineering is that soils and earthquakes are very complex phenomena that are driven by natural processes. Geotechnical engineering is often called a kind of “black magic” because, unlike most fields in engineering, we work with materials that are hidden from view and never behave exactly the same way twice.

We can’t see the soil and rock we design with, and their behaviour depends on an incredibly complex mix of geology, stress history, water, and time. So, we rely on a blend of science, intuition, and experience to understand and predict how the ground will respond, especially during earthquakes.

Why is it important to invest in natural hazards research like yours?

I think it’s really important for two main reasons.

First, New Zealand has lived through major hazard events that have had significant impacts on our infrastructure and communities. Investing in research helps us refine our models and design methods so we can better predict and manage those impacts for future events.

And second, New Zealand is really a natural earthquake laboratory. We have active faults, dense instrumentation, and an active research community. The data we can collect here are globally unique. So, by investing in natural hazards research, we’re not only making New Zealand more resilient, we’re advancing knowledge that can help the rest of the world too.

What is a misconception related to your research/field that you want to clear up?

The most common question I get when people hear that I am an earthquake engineer is: “When is the big one happening?”. The reality is that predicting exactly when an earthquake will happen is likely impossible, and that is generally not the goal of an earthquake engineer. Our goal, as ground motion specialists, is to predict what the spatial distribution and intensity of shaking would be if and when a particular earthquake occurs. Earthquake engineers then predict what the impact to the natural and built environment would be from that level of shaking.

The most common question I get when people hear that I am an earthquake engineer is: “When is the big one happening?”. The reality is that predicting exactly when an earthquake will happen is likely impossible, and that is generally not the goal of an earthquake engineer. Our goal, as ground motion specialists, is to predict what the spatial distribution and intensity of shaking would be if and when a particular earthquake occurs. Earthquake engineers then predict what the impact to the natural and built environment would be from that level of shaking.

What do you like to do for fun outside of work/study?

I am a passionate outdoorsman that enjoys tramping, fly fishing, hunting, mountain biking, packrafting, and just being outdoors in remote wilderness. Recently, my passion has changed slightly towards introducing my one-year-old son, River, to the great outdoors.

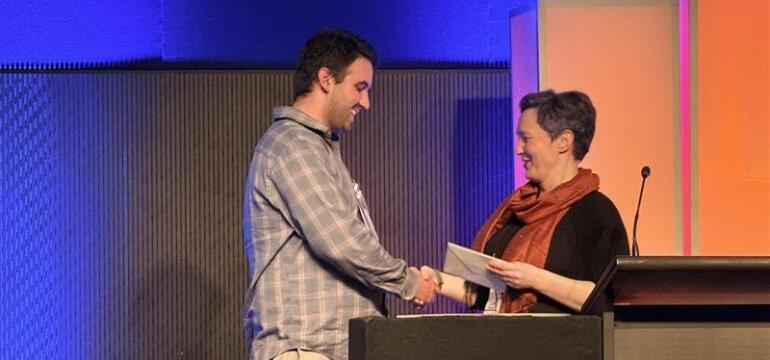

The main image shows Chris de la Torre winning "Best Research Paper" at the New Zealand Geotechnical Society symposium, October 2025, for his research into site responses.